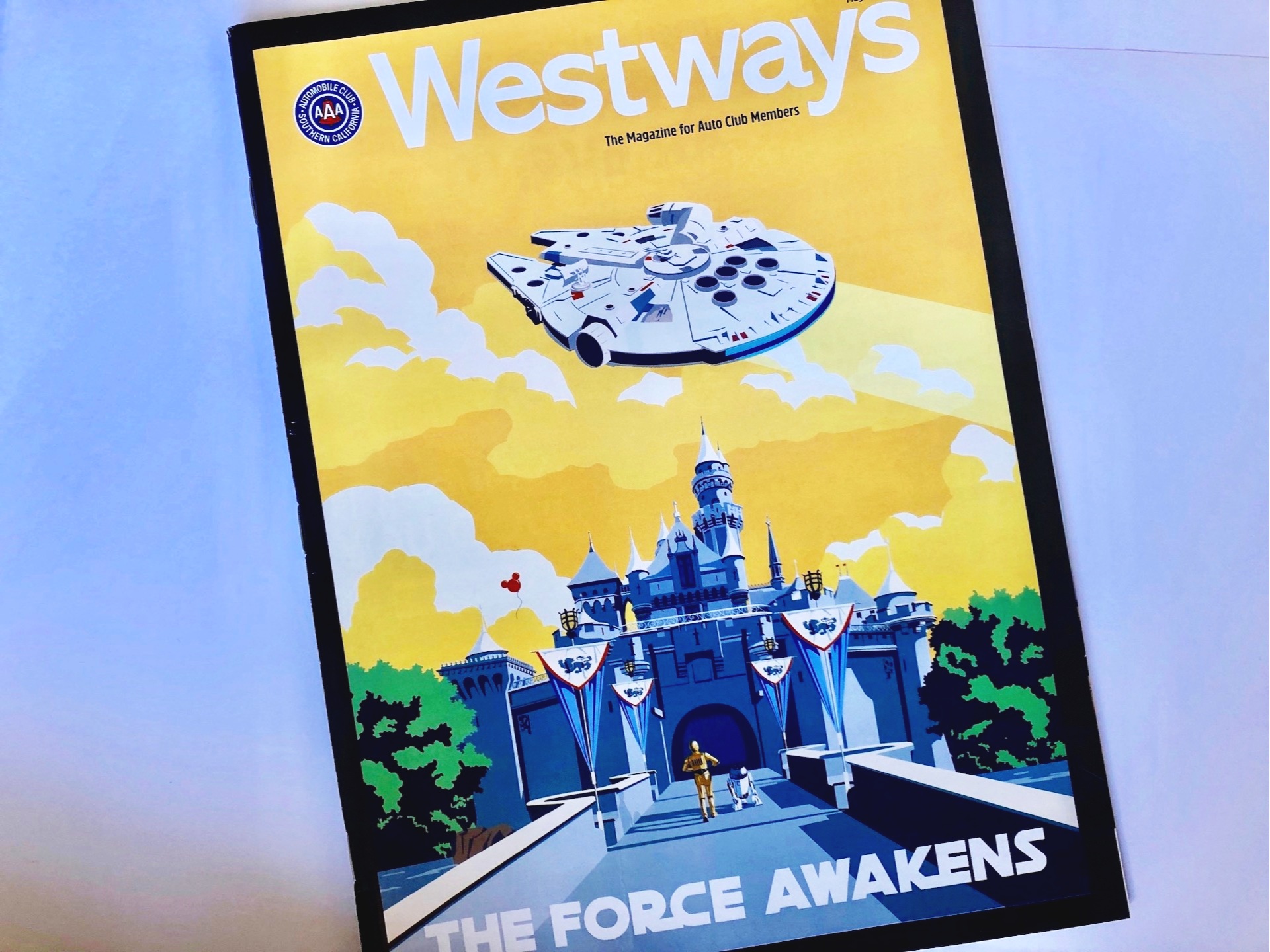

Tour de Force: The Making of Disneyland's Galaxy's Edge

By Jim Benning

Westways, March/April 2019

Chris Beatty is talking at light speed. Wearing a hard hat, a reflective vest, and jeans, the Walt Disney Imagineer is leading a tour of the 14-acre construction site at Galaxy’s Edge, the hotly anticipated Star Wars–themed land set to open at Disneyland on May 31. All around him—but hidden from parkgoers on nearby Big Thunder Mountain—workers are laying concrete, installing props, and generally hustling to complete the largest single-themed land that the park has ever created. Beatty dodges a patch of mud and sprints up a flight of stairs to a spot that overlooks one of the land’s star attractions: a life-size Millennium Falcon.

The ship that Han Solo and Chewbacca piloted away from stormtroopers on Tatooine in the original Star Wars more than 40 years ago, and that Rey and Finn commandeered to escape the First Order on Jakku more recently, has been brought to life in all its three-dimensional, battle-worn, hunk-of-junk glory. In fact, Millennium Falcon: Smugglers Run is one of two new Star Wars attractions designed to induce both awe and adrenaline. Beatty flashes a wide grin as he surveys the iconic ship and the weathered spaceport behind it. “This,” he says, “is one of the hero shots of the land.”

As one of about a dozen writers invited for this sneak peek, I’ve reminded myself to remain a dispassionate journalistic observer. But who am I kidding? The moment I spot the Millennium Falcon, I’m the 6-year-old at Josh Blaustein’s Star Wars–themed birthday party in 1977, eyes glued to the big screen, popcorn in hand, mouth agape. I’m the same kid playing with my toy Millennium Falcon and Star Wars action figures—don’t call them “dolls”—and imagining myself making the jump into hyperspace. So, yeah, seeing the ship before my eyes is very cool.

This Proustian response is exactly what Beatty and the other Imagineers intended when they started development on the land in 2014. Back then—two years after Disney shelled out a reported $4 billion to acquire Lucasfilm (including the Star Wars franchise)—Beatty and other Imagineers visited the film company’s headquarters in San Francisco’s Presidio. There, in the shadow of the Golden Gate Bridge, past the gurgling fountain topped by a wizened Yoda, a small team of Imagineers and Star Wars story developers considered a daunting question: How do you transform one of history’s most beloved movie franchises into a beloved amusement park land? (Make that two lands: A nearly identical version will open at Disney’s Hollywood Studios at Walt Disney World in Florida on August 29.)

The magnitude of the task wasn’t lost on Beatty, the executive creative director who began as an apprentice at Walt Disney Imagineering in 1997 and has since worked on projects from Florida’s Epcot to Disneyland Paris. An avowed Star Wars fan, the 47-year-old recalls unwrapping action figures as a kid on a Christmas morning in Ohio and bounding into his family’s snow-covered yard to build his own Hoth play set. “Think about the pressure,” he says, “to deliver on 40 years of people’s passion and their longing to step into these worlds and be a part of the Star Wars universe.”

A Long Time Ago

Of course, the Imagineers first had to determine which part of that sprawling universe to re-create. They considered familiar film settings such as Hoth, Endor, and Tatooine, but Beatty and the others saw risks in trying to reproduce, say, Luke Skywalker’s home planet. As Beatty explains: “You’ve seen it before, you’ve lived it before. It would never be as good as standing in line for the first time in 1977 to see the original film.”

As they mulled options, the Imagineers also met with J.J. Abrams, the phenom director-writer-producer behind Lost and Westworld. At the time, he was shooting Episode VII: The Force Awakens, and he’d soon be tapped to direct Episode IX. By the time the Imagineers returned to their Glendale campus, they’d come to a critical realization: Rather than re-create a world from earlier films, Beatty says, “maybe it’s better to lean forward into the future of the franchise, but leave a door open to the past.” (As someone who’s not ashamed to admit that images of R2-D2, C-3PO, Luke Skywalker, and Princess Leia adorned his bedding for the better part of a decade, I’m happy that door won’t be sealed entirely.)

The Imagineers decided to create Black Spire Outpost on planet Batuu. Named for the petrified trees that dot the land, the location has appeared in Star Wars novels but not films—at least not yet: Some fan websites predict that the outpost will make its big-screen debut in Episode IX, which is due to hit theaters in December.

Black Spire Outpost wouldn’t seem an obvious choice. Once a thriving refueling stop at the galaxy’s outer reaches, it has fallen in prominence—“kind of an old Route 66 story,” says Scott Trowbridge, lead Imagineer on the project. The village is now a haven for smugglers, bounty hunters, and other ne’er-do-wells. It’s dangerous and mysterious, yet it also presented Imagineers with a kind of narrative blank slate: Because fans don’t associate Batuu with Luke or other marquee characters, Trowbridge says, the location gives visitors a better chance to “live their Star Wars story.”

With that key decision behind them, the team began considering how to bring the new land to life—what Imagineers call “physical storytelling,” or “narrative place-making.” What should Batuu look like, feel like, and sound like? Designers would draw on Star Wars films’ distinctive visual vocabulary—the familiar color palette of the First Order, for example, and the triangle shapes of Star Destroyers. But they also wanted to ground the land in actual places on Earth, which Lucasfilm execs say has been critical to achieving Star Wars’ timeless feel.

Batuu has been around for millennia, according to the saga, so Beatty and other Imagineers traveled to Istanbul, Turkey, and Marrakech, Morocco, to find visual cues that could help imbue the land with a sense of ragged history. By their own admission, the traveling band of Imagineers drove local tour guides crazy. The guides wanted to show off mosques and ancient temples, but as Beatty recalls, “They’ll turn around and we’re taking pictures of doorknobs and rusty wires up on a building that looks like a rat’s nest.” He points to a photo the team took of an electrical box plastered onto a leaching, weather-stained wall—an image that has helped guide the look of the buildings. The black spires, meanwhile, were inspired by rock formations in Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park.

Back at the Glendale campus, as initial plans were coming together, the team donned virtual reality goggles to experience the feeling of walking through the new land. By using such virtual reality technology, the Imagineers could make adjustments to maximize the impact of key viewpoints—what Beatty calls “reveals.”

An example is the tunnel that will usher parkgoers from Frontierland into Galaxy’s Edge—one of the land’s three entrances (only two will lead into Florida’s version). “As you come through, there’s a moment where we reveal a little bit of the architecture,” Beatty says. Visitors will see spires in the distance, but trees will obscure part of the view. That, he says, is by design—to provoke visitors’ curiosity and sense of adventure. If you then turn left as you come out of the tunnel, he adds, “You see spaceships and domes and canopies billowing in the wind. Just like in a film, we’ve framed that establishing shot.”

The goal at every turn, Imagineers say, has been to create Disney’s most ambitious, immersive, and interactive land ever. Cast members—some Batuu citizens, some Resistance sympathizers hiding out here—will wear distinctive ensembles. New music written by John Williams, the Academy Award–winning composer behind the original Star Wars theme, will play at key moments. The Disney Play Parks mobile app will allow for interactive experiences. And visitors will find food, drinks, and merchandise designed exclusively for the new land.

The Kessel Run

All of this preparation has fans’ anticipation running high—and security at the construction site Death Star–tight. Before I can tour the land, I have to promise not to take photos or even carry a smartphone into the area. I pull on a hard hat, boots, and a reflective vest and am soon strolling past weathered domes and petrified trees. I’m led inside Oga’s Cantina, where construction crews are hard at work, and then through part of Star Wars: Rise of the Resistance, a trackless ride that puts parkgoers into battle with the First Order. That, too, is still being finished, and Disney says it won’t open until later this year.

To my delight, I also come face to face with the Millennium Falcon. Imagineer Asa Kalama leads our group through the attraction’s queue, where an animatronic Hondo Ohnaka seek s volunteer parkgoers to deliver cargo. Then comes the moment I’ve been waiting for: We walk onto the ship itself, first into a gloriously re-created Chess Room, and finally, into the cockpit. It looks just as it does in the films, with control panels lining the walls. I can practically hear Han Solo yelling, “Traveling through hyperspace ain’t like dusting crops, boy!”

I settle into one of the six seats, soak in the oddly familiar scene, and recall something that Imagineer Margaret Kerrison said earlier: “When we open Galaxy’s Edge, I think grown men are going to cry. … There’s just so much anticipation and excitement for this.”

Indeed, the attraction isn’t even finished yet and I’m already getting a little misty. The galaxy that was once far, far away feels—amazingly—much, much closer to home.