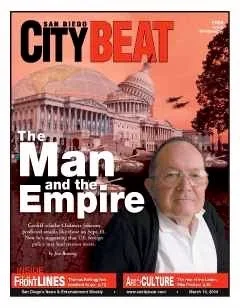

The Man and the Empire

By Jim Benning

San Diego City Beat, Cover Story, 2006

Author Chalmers Johnson was asleep in his San Diego-area home on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, when the telephone rattled him awake.

Metropolitan Books publicist Tracy Locke was on the line from her Manhattan office two miles from Ground Zero. The previous year, she had promoted Johnson’s book, Blowback: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire, which warned that U.S. policies abroad were creating the potential for retaliatory attacks. “Blowback” is the term the CIA uses to describe the unintended consequences of covert actions.

The book had generated only modest interest when it was published, but with the events of the morning, Locke knew that was about to change. Before rushing home, she spoke into the telephone in a voice flattened with shock, telling the author, “Turn on your television. The World Trade Center has just been hit. The worst kind of blowback has happened.”

Johnson was stunned. He hadn’t exactly predicted the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in the book, but he had come close. “World politics in the twenty-first century,” he wrote, “will in all likelihood be driven primarily by blowback from the second half of the twentieth century — that is, from the unintended consequences of the Cold War and the crucial American decision to maintain a Cold War posture in a post-Cold War world.”

Blowback shot up bestseller lists and was reprinted thirteen times as Americans struggled to make sense of the attacks. Impressed with Johnson’s prescience, the German magazine Der Spiegel labeled him the “California Cassandra” after the mythological Greek prophesier who often went ignored. Johnson had more to say, however. In January 2004, his follow-up book hit stores and soon landed on bestseller lists. The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy and the End of the Republic rails against America’s vast military presence abroad and warns that more harm is on the way, including perhaps the end of the republic itself, if the nation does not rein in its military and change its aggressive posture.

Neoconservative thinkers behind the Project for the New American Century would beg to differ with Johnson’s analysis, of course, but many others have embraced the book. The Los Angeles Times and the San Diego Union-Tribune praised it, and writers as diverse as William Greider of The Nation and James Fallows of The Atlantic Monthly have voiced their enthusiasm. Wrote Fallows: “Chalmers Johnson’s relentless logic, authoritative scholarship, and elegantly biting prose distinguish the Sorrows of Empire, like all his other work.”

Author Noam Chomsky agrees. “I think his work is excellent,” he told me. “He’s picking up the most important topics.”

Suddenly, at the age of 72, the retired political science professor finds himself a leading critic of U.S. policies abroad, and a strong new voice from the left. In recent months, Johnson has published articles in Harper’s and the Sunday Los Angeles Times opinion section. He has traveled the West Coast, speaking to standing-room-only crowds. At his home overlooking the Pacific, he fields questions from journalists the world over inquiring about his perspective on the American empire — a term Johnson insists must now be used.

“Americans may still prefer to use euphemisms like ‘lone superpower,’” he writes, “but since 9/11, our country has undergone a transformation from republic to empire that may well prove irreversible.”

Empire Revealed

It’s an unexpected personal transformation for a man who once worked as a consultant for the CIA, supported the Vietnam War as a professor at UC Berkeley, and who described himself just 15 years ago as a staunch “cold warrior.” If the turnabout isn’t unlikely enough, Johnson is carrying forth his message from San Diego County, which is hardly a hotbed of dissent, or even modest countercultural enthusiasm. “In Berkeley, they put up mildly obscene statues,” Johnson remarked recently. “You come down here to San Diego and the idea of public art is an anchor painted white lying around on the grass somewhere.”

Yet, on a cool January evening, there was Johnson at The Book Works in Del Mar, a mile from the historic racetrack, facing a crowd of eager listeners. At least 100 locals had endured rush-hour traffic to hear him speak. They filled rows of chairs and stood elbow-to-elbow at the bookstore’s coffee counter. They collected several deep in doorways and peered in through the front window. Steadying himself with the help of a cane, Johnson waited in the wings as his literary agent, Sandra Dijkstra, introduced him.

“In these times especially, we need angry people,” she told the audience, made up largely of men and women well into mid-life. “We need people… who will call a pig a pig…. If you saw Chalmers’ L.A. Times op-ed recently, you saw that it said next to his name ‘Cardiff-by-the-Sea.’” She paused and scanned the San Diego crowd, then added with satisfaction, “It shows that people can have radical thoughts by the sea.”

As the audience broke into applause, Johnson approached the microphone. Wearing gray slacks and a dark sweater, with short dark hair and piercing eyes behind big round glasses, he looked every bit the retired university professor. He spoke in a deep, resonant voice of his longtime support for America’s military during the Cold War. He noted his consulting work for the CIA during the 1960s and 1970s, when he was asked to critique intelligence estimates. If anyone doubted Johnson’s cold-warrior credentials, or wanted to dismiss him as an old Berkeley lefty, he wasn’t about to hear it. The former Navy officer eyed the audience, cracked a sly smile and said, “Anybody who wants to play security clearance with me, I’ll beat you.”

With that, Johnson launched into a critique of the Bush administration and U.S. foreign policy: How could President Bush have asked Congress after the Sept. 11 attacks, “Why do they hate us?” He needed only to look at members of his own administration, Johnson said, who had served in previous administrations that supported the likes of Manuel Noriega, Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden. “It’s a remarkable litany of characters we have decided have worn out their usefulness for us,” he said.

Johnson spoke of the many military bases the U.S. maintains around the globe and the animosity the bases engender in so many countries. He could understand such a strong global military presence during the Cold War, when the U.S. needed to contain the spread of communism. But why did the U.S. continue to maintain such a vast military presence at such a high cost? There was only one answer, he said: empire.

How would Americans feel, he wondered, if they found themselves in the position so many citizens of other countries are now? “If we had a division of Turkish troops in San Diego,” Johnson said, “we’d have a few patriotic young [American] men who would kill a couple [of Turks] every weekend.”

Johnson said he fears America’s aggression will come back to haunt the country. He spoke of the rise of China and the costs of the U.S. military bases. He invoked the fall of the Roman Empire and recalled how rapidly the empires of Japan, Germany and the Soviet Union had fallen in his own lifetime. He worried about the military industrial complex, which he fears will only grow stronger and more dominant in guiding U.S. policies abroad in the years to come. “I’m 72 years old,” he said. “Given the pace of events, I think there’s a good chance I’ll live to see the end of the American empire.”

When Johnson asked for questions, one woman wondered how he could offer such a grim forecast with so little hope. Johnson nodded. He had heard the complaint before. “My wife keeps saying to me, ‘You cannot go on without ever having a hopeful message,’” he said. The truth is, Johnson isn’t too optimistic, but he maintains a sense of humor.

“Plan your escape route,” he has joked. “Think about Vancouver.”

Johnson conceded, however, that all is not yet lost. He said he believes change would have to come from the grassroots level. He spoke of the anti-globalization protests that began in Seattle in 1999, as well as the millions around the world who protested the war in Iraq. There is still cause for hope. “It’s not to say that this couldn’t be turned around,” he said. That, after all, was one of the reasons he wrote the book.

New Information

Fifteen years ago, Johnson wouldn’t have dreamed of delivering such a talk. On a sunny afternoon several days after his bookstore appearance, Johnson sat in his living room in Cardiff, surrounded by Asian art he had collected over the years, and discussed his transformation. During much of the Cold War, Johnson was a political science professor on the Berkeley and San Diego campuses of the University of California. He specialized in China and Japan, and wrote more than a dozen academic books on the region. Although many of his Berkeley students protested the Vietnam War, he backed it. He continued to support America’s containment policies throughout the Cold War. “I regarded the Soviet Union as a menace,” he said. “I felt that it was a matter of national security for us to counter it.”

Then came 1991 and the demise of the Soviet Union. “I was shocked by our country’s reaction,” he said. “I expected a much larger peace dividend. I expected a demobilization of our massive Cold War apparatus. I believe we behaved outrageously, in the sense that our government began immediately to search for a replacement enemy: China, instability, drug wars, terrorism, damn near anything they could find.” Johnson reassessed where he stood. “It raised the question,” he said, “Was the Cold War a cover for a deeper and more fundamental American imperial project?”

He concluded that it was, and he changed his views on a wide range of issues, including the Vietnam War. Johnson has a favorite explanation for his reversal. “When someone once accused the economist John Maynard Keynes of being inconsistent, Keynes responded, ‘When I get new information, I change my position. What, sir, do you do with new information?’” Johnson grinned. “That is the point,” he said. “I got some new information.”

Johnson’s willingness to change his views impressed many who know him. “You could go through those years since the Vietnam War looking for people of his background who had reversed their positions on Vietnam and not find any,” said Tom Engelhardt, Johnson’s editor at Metropolitan Books.

One of Johnson’s former Berkeley students, E.B. Keehn, 48, now a clinical psychologist, is equally admiring. “Chalmers is that rare public intellectual who bases his views on information and striving for the truth, and who is willing to adopt new views,” he said.

Keehn recalled Johnson as a wildly popular professor whose classes filled quickly and who routinely attracted long lines of students outside his office. “It wasn’t just that he could answer any question thrown at him,” Keehn said, “but his answers would always include a thorough presentation of all the possible theories and conclude with which theory was most likely. People would sit back and say, ‘Wow, I don’t have an intellect like that.’”

That uncannily sharp mind is no less apparent these days. Back in his living room, holding forth for a moment on what he sees as the sorrows of globalization, Johnson complained that policies at institutions such as The World Bank are tied too closely to U.S. interests. Without missing a beat, he said, “The World Bank is located at 1818 H Street Northwest in Washington, not far from the Treasury Department.”

Ace of Bases

Johnson retired from academia in 1992 and founded the Japan Policy Research Institute, over which he still presides, publishing books and academic papers. It was in Japan in 1996 that Johnson had another revelation that would shape his worldview. He traveled to Okinawa at the invitation of the island’s governor to speak about the U.S. presence after a 12-year-old Japanese girl was raped by two American marines and a sailor. The U.S. has maintained a military presence on Okinawa since 1945. Even though Johnson had studied Japan extensively, he hadn’t paid much attention to U.S. bases on the island, or to U.S. bases anywhere. “I was shocked by what I saw,” he said.

Johnson was surprised to learn that the U.S. maintained 38 military bases on Okinawa, an island smaller than Kauai. Military personnel had exclusive access to beaches, golf courses and other recreation facilities on prime real estate, Johnson said. If that wasn’t enough, Johnson discovered that, but for the age of the girl, the recent rape wasn’t an aberration. The rate of sexually violent crimes committed by American troops leading to court marshal on Okinawa, he said, was averaging about two per month and had been since 1945.

The Japanese he spoke with were openly resentful of the U.S. presence, and Johnson could see why. “There were 1.3 million Okinawans living cheek-by-jowl with war planes, the Third Marine Division and environmental pollution,” he said. “I am not anti-Marine. I attended assault boat school at Camp Pendleton in 1954. But in my view, we shouldn’t be there.”

Johnson believes the U.S. shouldn’t be in a lot of places. He suspects many in the Bush administration who are crafting the nation’s foreign policy are operating on misconceptions about the reasons the Soviet Union collapsed and the U.S. became the dominant power. “I believe they erroneously concluded that we had won the Cold War,” he said. “We simply didn’t lose it as quickly or badly as the Soviet Union did because we were inherently richer. But I personally believe that we are today afflicted by many of the same problems that brought down the Soviet Union.”

That conclusion led Johnson to write The Sorrows of Empire, published as part of Metropolitan Books’ The American Empire Project, which also includes Noam Chomsky’s latest book, Hegemony or Survival.

Angered by the Bush administration’s aggressive response to the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, as well as the large number of bases the U.S. continued to maintain around the globe, Johnson set out to explore U.S. militarism and its dangers. The distinction between the military and militarism is critical, he said. He supports a strong military.

“But militarism doesn’t mean the defense of the country,” he said. “It means a deep fundamental vested interest in the military as a way of life, as a way of making money, as a secure form of state socialism, of expansion into areas usually thought of as off the reservation for the military.”

In researching the book, Johnson studied the Department of Defense’s Base Structure Report and other government documents to gauge the extent of the military presence abroad. According to the Defense Department, as of September 2001, the U.S. was deploying 254,788 military personnel in 153 countries, Johnson writes. It maintained 725 foreign bases in 38 countries. The reports paint a portrait of a nation dominating the globe through military force to a degree most Americans fail to appreciate, Johnson believes.

“Due to government secrecy, they are often ignorant of the fact that their government garrisons the globe,” he writes. “They do not realize that a vast network of American military bases on every continent except Antarctica actually constitutes a new form of empire.” The nation’s military dominance extends well beyond planet earth these days, Johnson hastens to add, because the U.S. is now militarizing outer space.

This imperial quest did not begin with the current Bush administration, Johnson said, but he believes the situation has grown more dangerous since the World Trade Center attacks, and particularly since the U.S. invasion of Iraq. “The Bush administration is now creating conditions in which any nation on earth has got to think, if the U.S. juggernaut starts to come after us, what will stop them?” he said. “The conclusion they’re inevitably drawn to is that what was wrong with Saddam Hussein was not that he had weapons of mass destruction. He didn’t have them. When a nation actually has them, the U.S. pays attention, as in the case of North Korea.”

That fact, Johnson fears, will inspire other nations to develop nuclear arms for self-defense. “These policies have produced a catastrophe of nuclear proliferation around the world,” he said.

The end of the republic could result from four potential consequences of all this, Johnson believes: The Pentagon could play an increasingly prominent role in foreign policy, which could lead to perpetual war and more terrorist attacks. As security becomes a greater concern, U.S. citizens would lose more of their constitutional rights. To counteract declining morale, propaganda glorifying war and power would increase. And, finally, the escalating costs of the war machine could simply drive the nation into bankruptcy.

Not surprisingly, some critics take issue with Johnson’s analysis, or at least aspects of it. Andrew J. Bacevich complains in the Washington Post that The Sorrows of Empire muddles history and fails to clarify who is responsible for the rise of American militarism. “Thus, history considerably complicates the question of assigning responsibility for what Johnson clearly views as a perversion of U.S. policy,” Bacevich writes. “Indeed, it suggests the possibility that a militarized policy may not be a perversion at all, but an authentic expression of American statecraft.”

Writing in Foreign Affairs, G. John Ikenberry argues that Johnson sees imperialism in everything the U.S. does. “Ultimately,” Ikenberry writes, “it is not clear what the United States could do — short of retreating into its borders or ceasing to exist — that would save it from Johnson’s condemnation.”

Johnson concedes that he could be wrong about all this. Perhaps U.S. militarization doesn’t pose a threat. Maybe the United States will indeed spread democracy and prosperity around the globe until all nations coexist peacefully. Johnson doubts it, but if he is proven wrong, he said, that’s just fine with him.

Leaning back in his chair, the “California Cassandra” glanced out the window at the fading afternoon light, considered the possibilities and smiled. “If I’m mistaken, you’re going to forgive me,” he said. “You’re going to be so pleased I was wrong.”